Opinion polls suggest Chega could become Portugal’s third-largest party in the country’s legislative elections on 10 March. Luca Manucci and Steven M. Van Hauwaert assess the roots of the party’s support.

Since 2019, Portugal has joined the list of European countries where the populist radical right manages to elect representatives in the national parliament. Until a few years ago, the country was considered a key exception to this trend. We can now safely say this is coming to an end due to the success of Chega (Enough).

Chega obtained one seat in the 2019 Portuguese legislative elections (with the election of former candidate for the centre-right PPD/PSD and party leader André Ventura) and 12 seats in the 2022 elections. For the upcoming legislative elections on 10 March, they are polling around 18%, which would make them the third-largest party and – much like Vox in Spain – a political force that traditional parties will have to account for.

The context for the upcoming elections is a particular one. Portugal is going to the ballot box after a political scandal. Following a police probe (Operation Influencer), on 7 November 2023, several high-ranking politicians were indicted and arrested on charges of corruption and malfeasance in relation to a variety of business deals where the government had a stake.

Only days later, on 9 November 2023, socialist Prime Minister António Costa (Partido Socialista – Socialist Party), whose party had an absolute majority, resigned, and stepped down from his party leadership position. Consequently, the government fell, and President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa called a snap election.

The role of Chega

Chega is set to be one of the primary parties that capitalises on the scandal because it has long accused the socialists of corruption. Well before the November 2023 scandal, Lisbon was full of Chega posters arguing that Portugal needs cleansing, with four socialist politicians crossed out. In this scenario, the anti-establishment rhetoric of Chega can reach a broad audience, especially among those who do not have strong party affiliations and who are less satisfied with the way democracy works (or, more specifically, with what Richard Katz and Peter Mair term the Portuguese “cartel parties”).

Since its formal emergence in 2019, Chega has transitioned, in just a few years, from a marginal political actor to a party that might soon be included in the government formation process. The Centre-right PSD (Partido Social Democrata) has ruled out forming a government with Chega, but analysts are sceptical about whether this will hold true.

Among the public, members of the media and politicians from traditional parties, there are similar fears to those that characterised the 2023 Spanish elections, when Vox was polling around 15% and eventually received 12% of the vote to become the third-largest party with 33 seats in the Cortes Generales (nonetheless a loss of 19 seats). Given traditional right-wing parties are willing to consider a coalition with Chega, the party’s role in Portuguese politics is likely to become more consolidated after the 2024 election, not to mention the upcoming European Parliament elections in June 2024.

Since its emergence in 2019, we have come to know a lot about Chega, from their message to their electorate. This puts us in a position to start understanding and explaining its emergence. Here, it is important to pay attention to a particular factor that distinguishes Portugal from most other European countries, namely its authoritarian past. Previous scholarship has focused on how this past might shape the political space and political opportunities for parties reflective of such a past.

Yet, what we remain quite oblivious about is whether (and how) the authoritarian past also plays a role for citizens. Do Portuguese citizens share a particular appreciation for the authoritarian past? To what extent are they nostalgic for that authoritarian past? And, more importantly, to what extent are these feelings more prominent among Chega supporters? Do they differ from more traditional party supporters in that regard and if they do, what does that mean for Portuguese democracy and its future?

Chega and nostalgia for the authoritarian past

We collected original survey data in Portugal between November and December 2023 (a representative sample of 1,500 people), in the context of the POLAR project. As part of this project, we developed and fielded nine innovative items to help us capture to what extent Portuguese citizens are nostalgic for their authoritarian past, and more precisely the right-wing dictatorship of António Salazar and his corporatist regime entitled Estado Novo.

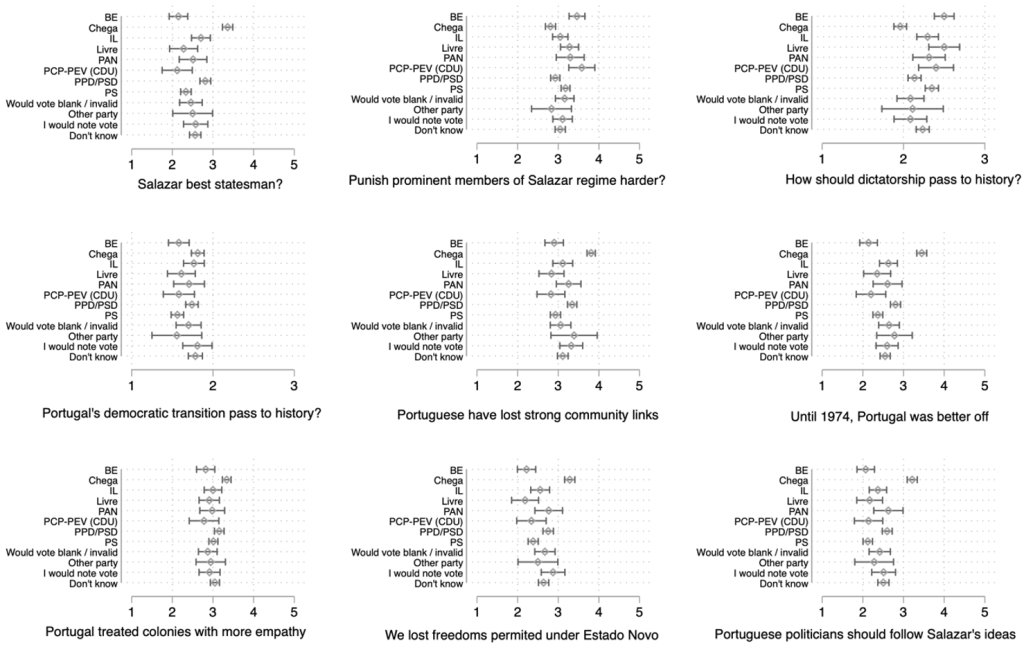

We include these items in Table 1. The initial two items ask about citizens’ evaluation of the past (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The third and fourth items ask how the dictatorship and the democratic transition should pass to history (1 = more positive than negative aspects; 2 = as many positive as negative aspects; 3 = more negative than positive aspects). The last five items ask about various aspects of respondents’ nostalgia (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

Table 1: Nostalgia items

Figure 1 outlines the averages alongside each of these items, separated by party support. This allows us to get a general understanding of where Chega supporters stand in terms of nostalgia compared to some of their “traditional” counterparts.

Specifically for five of the nine items, Chega supporters stand out. First, they are more likely to agree that Salazar is one of the best statesmen in the history of the country (item 1). Chega supporters are also more likely to agree that since the democratic transition, the Portuguese have lost the strong community links that tied them together (item 5) and that they were better off during the authoritarian past because the country was based on traditional values and national identities (item 6). Despite living in a liberal democracy, Chega supporters are more likely to feel like they lost some freedoms compared to Estado Novo (item 8) and that the country would regain some of its former glory if politicians would follow Salazar’s ideas (item 9).

Figure 1: Individual nostalgia items, averages by party

These latter observations (related to items 8 and 9) are particularly relevant, as they highlight that the ideas and values of the authoritarian regime are not only seen through a set of pink nostalgia glasses, but it is even considered a recipe for a bright future – at least by an important portion of the electorate.

In Spain, this is often described as Sociological Francoism, which refers to the endurance of revisionist myths about the dictatorship. For example, there is a widespread idea that some freedoms that were permitted by the Francoist regime, such as smoking in public places or barbecuing in the mountains or the beach, have been taken away. Our analysis, therefore, provides a first indication of what we could then refer to as Salazarismo sociologico among Chega supporters – something we were previously not aware of, at least not this explicitly.

Some of the other items do not really divulge clear differences between Chega supporters and their counterparts. This is perhaps surprising, but it might speak to a larger acceptance of some of the nostalgic references across Portuguese politics. What is perhaps also worth pointing out here is that Chega supporters not only differ from other party supporters in their appreciation of the authoritarian past but also from those who would not go out and vote. This further supports the idea that populist radical right supporters are intrinsically different from disgruntled and apathetic citizens who choose not to go out and vote. In other words, it is another small piece of evidence that populist radical right supporters are more than just protest voters.

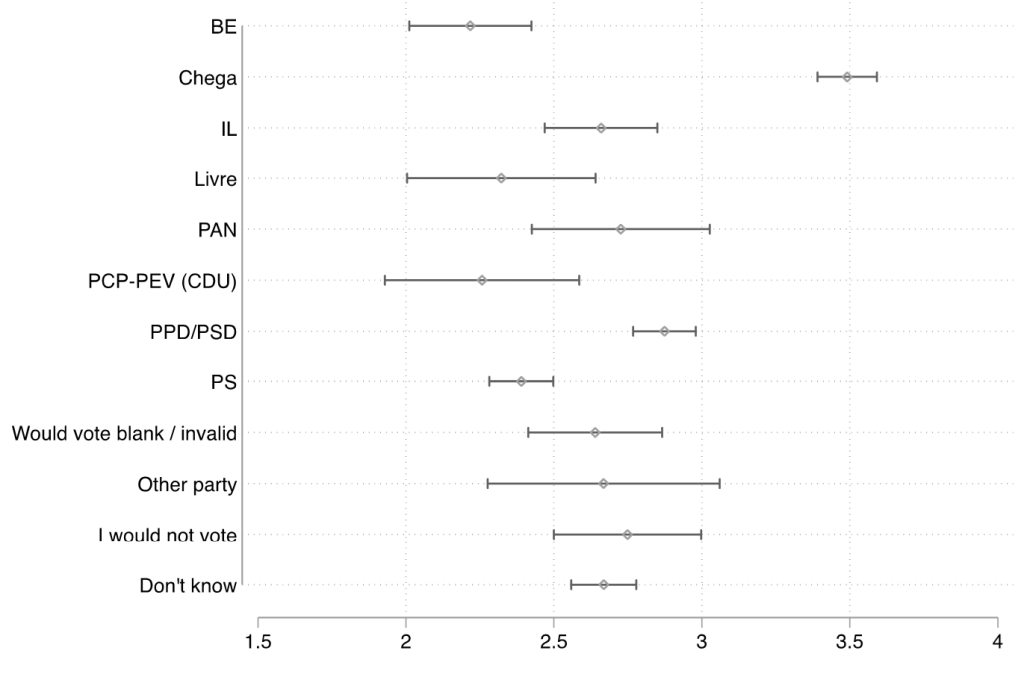

Drawing from this initial overview, we can examine whether these different items actually gauge the same concept. We designed them as separate indicators of nostalgia towards the authoritarian past. If we do a simple polychoric factor analysis of the 9 items, we find that they load quite nicely on a single factor (EV = 3.78). We estimate that factor and differentiate this again by party in Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows how much Portuguese party supporters are nostalgic about their respective authoritarian regimes. Those who declare they will vote for Chega in the next election are on average more nostalgic compared to those who would not vote for Chega. The fact that Chega supporters are the most nostalgic compared to all other citizens is quite clear. The differences between all other parties, as well as non- and other-party voters, remain otherwise indistinguishable from one another. This further supports our earlier claim that nostalgia might be quite commonly accepted across the Portuguese political landscape, but that Chega supporters nonetheless stand out in this regard.

Figure 2: Aggregated 9-item index of nostalgia, averages by party

Back to the future?

The leaders of Chega carefully play with the authoritarian nostalgia of Portuguese citizens. They use dog whistle tactics to signal that they are in line with the ideas and values of the authoritarian past, without compromising their democratic credentials by endorsing openly Salazarist symbols.

For example, Chega’s leader, André Ventura, chose as the party’s motto the same words that characterised Salazarism: “God, Fatherland, Family”. By adding the word “Work” at the end he can claim that Chega’s motto is different from the one of Estado Novo. While this is technically true, it is not particularly subtle, and his electorate will easily see the continuity between the authoritarian past that they are so nostalgic for and today’s populist radical right.

In the next months and years, the debate about the democratic credentials of Chega will continue, especially if they do well in the upcoming elections and if they become necessary to form a government. While their immediate goal is neither to dismember democracy nor to create a new authoritarian regime, cases like Hungary, the UK and the United States show us what populist radical actors can do once in power. They go against minority rights, media freedom, separations of power and the rule of law.

The fact that Chega voters are so nostalgic for Salazar’s authoritarian regime leaves no doubt as to what they want. They are nostalgic for the authoritarian past and this nostalgia will be an important factor in voting for Chega in the 10 March elections. In 2024, exactly 50 years since the Carnation Revolution, this is not a detail but a reminder. Authoritarian legacies influence the present and can decide the country’s future.

This article presents findings from the POLAR project (Back to the Future? Populism and the Legacies of Authoritarian Regimes), funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (2022.03115.PTDC).

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Alya Kuznetsova / Shutterstock.com

Discussion about this post