The European Commission has proposed a package of measures to protect Europe’s steel industry from the impact of high costs, reduced demand and cheap competition. Tobias Hofelich and Tobias Kopf write that 75 years after the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community, these efforts to protect the steel industry could once again trigger a new phase of European integration.

In 2025, the European Union celebrated the 75th anniversary of the Schuman Plan which gave birth to the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and set the foundations for European integration. But while the EU held various festivities, steel industries across Europe have little reason to be cheerful.

The original six members produced a combined 19% of the total global output of steel in 1952, the ECSC’s first year of operation, whereas today’s 27 EU member states only reached a combined 7% of global output in 2024. European steelmakers suffer from a global supply shock and struggle to compete with Chinese producers, who are responsible for 54% of global output. Their competitive advantage results mostly from sizeable state subsidies as well as lower energy and labour costs.

In response, the European Commission has proposed to protect domestic steel mills from global competition by raising trade barriers, cutting almost in half its tariff-free import quotas and doubling the out-of-quota duty to 50%.

The proposed measures would extend the EU’s anti-dumping instruments in place since 2016 and directly target market distortions from subsidies in third countries. In December 2025, the Council adopted the proposal with only modest changes, paving the way for negotiations with the European Parliament.

Compared to 75 years ago, the parameters have shifted. Instead of supporting a strong steel sector and thereby containing national military buildup, the EU’s current initiative aims at rescuing an ailing industry while member states are rearming against the backdrop of heightened geopolitical tensions.

What remains the same is that the proposed solutions are distinctly European and require member states to rethink old paradigms. This becomes abundantly clear in public debates in Germany, the EU’s largest steel producer, where leaders increasingly consider strategic geoeconomic aspects alongside long-standing free market principles.

German “steel summit” commits federal government to protectionist measures

With 37.2 million tons of output in 2024, German steel accounts for about 28.7% of the EU’s total output. Germany’s historically strong steel sector is facing pressure to reduce CO2 emissions, while energy prices have soared and cheaper imports outcompete domestic production.

On 6 November 2025, Chancellor Friedrich Merz hosted a so-called “steel summit” to discuss solutions with representatives from the steel industry and labour unions. The government expressed support for the Commission’s proposal and committed to taking action in four areas: improved trade protections, lower energy costs, support for climate-friendly steel production and protection of the European market.

These points largely echo the demands made by domestic steel producers and build on existing policies such as industrial energy subsidies, in effect since 1 January 2026. Despite falling short of new policy ideas, the steel summit embodied a new urgency. Reminiscent of former ECB president Draghi’s pledge to do “whatever it takes”, Chancellor Merz was cited saying “politicians must do everything in their power to preserve the industry”.

With similar pathos, his deputy and minister of finance called for more “European patriotism” and “buy European” initiatives, accelerating the debate on local-content requirements (LCR) which effectively promote discriminatory procurement practices based on country of origin.

Ultimately, what was agreed upon with the steel industry marks a turn away from ordoliberal economics and towards market intervention and protectionist trade policy. The proposed measures essentially mimic the Chinese approach of subsidising local producers and shutting out foreign competition.

The German Social Democrats (SPD), the junior coalition partner in the current government, even went as far as to suggest partial nationalisation as a measure of last resort. All this is hard to reconcile with the German economic tradition of rules-based market liberalism – especially for the conservative, CDU-led government.

Liberal market ideals are giving way to geoeconomic thinking

From a purely economic perspective, the proposed policies raise concerns. Clemens Fuest, president of the influential ifo Institute, has criticised the German government’s agenda setting regarding the highly publicised steel summit.

He points out that the amount of political attention did not reflect the sector’s actual economic relevance. Indeed, the market valuation of the German steel industry is only about €5bn. Considering opportunity costs, extensive policy interventions consume political, administrative and budgetary resources that could be used more effectively elsewhere.

Regulating primary inputs to limit cheaper imports is likely to exert upward pressure on prices. As a result, downstream steel processing industries such as the automotive and construction sector would suffer from higher input costs. This, in turn, creates additional regulatory pressure to contain price inflation and safeguard the competitiveness of downstream industries from adverse spillovers.

As a result, the interplay of market distortions and calls for subsidies risk evolving into a self-reinforcing cycle. The EU has already opened the door to the inflationary use of state subsidies through instruments such as the Net-Zero Industry Act. This logic may now be expanded further through local-content-requirements such as European preferences, introduced with initiatives like the Clean Industrial Deal and the Industrial Decarbonisation Accelerator Act.

Finally, raising import barriers risks retaliatory measures from trade partners. China has only recently tightened its Foreign Trade Law to that end and regularly uses its economic clout against adverse trade practices.

Germany is particularly vulnerable to foreign trade restrictions. Its export-oriented economy relies on open markets and its manufacturing sectors have become increasingly dependent on critical minerals sourced mostly in China. Direct hits against Chinese steel may, thus, prove perilous for other key sectors of German industry.

Aware of these economic and political pitfalls, the German government’s rhetoric increasingly incorporates geoeconomic considerations, emphasising supply chain resilience and strategic autonomy alongside its commitment to free trade.

In the words of Chancellor Merz: “the days of open markets and fair trade are, unfortunately, over”. Correspondingly, the German government has repeatedly criticised China’s trade practices and threatened retaliatory measures against US tariff hikes. After the geopolitical awakening dubbed “Zeitenwende” and the sudden departure from Germany’s “debt brake”, this marks a shift towards targeted protectionist policies, driven primarily by geoeconomic concerns.

Where does this leave Europe?

The protection of European steelmakers is a reaction to a changing global landscape. Despite technological advances, steel remains the key resource for the defence industry and is therefore vital for Europe’s objective to bolster defence capabilities in the face of an increasingly unstable international order. The ability to produce steel is thus a geopolitical as much as an economic issue and a critical component of the oft-mentioned goal of attaining strategic autonomy.

At the same time, the EU must not abandon its commitment to free trade, on which much of its normative power and economic success is built. On the one hand, defensive trade instruments can be rules-based, temporary and subject to strict conditionality. On the other hand, the EU should open its domestic market to likeminded partners whose producers operate under comparable regulatory and competitive conditions.

The dismantling of non-tariff barriers could help counterbalance an increasing policy focus on subsidies and reduce the risk of entrenched interventionism. Thus, protectionist and demand-oriented policies could be complemented by supply-side measures that restore competitive pressures and increase resilience through an integrated market.

The UK has already shown interest in working even closer with the EU on steel. Canada and Japan, allied and sharing the EU’s high labour standards and commitments to reduce emissions, would make other natural partners.

Altogether, the steel industry may once again set the stage for decisions driven by more than economic rationales and trigger a new phase of European integration. Within the EU, the protection of domestic steel could spill over to other critical sectors and spark a new sense of unity among its member states.

Moreover, the partial and sector-specific integration of likeminded allies into the EU’s common market would solidify Europe’s strategic position in an increasingly volatile international order.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of LSE European Politics or the London School of Economics. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group or any institution with which the authors are affiliated.

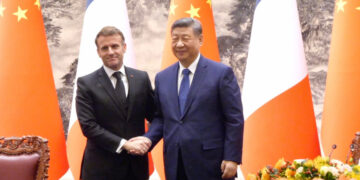

Image credit: uslatar provided by Shutterstock.

Discussion about this post