Story highlights

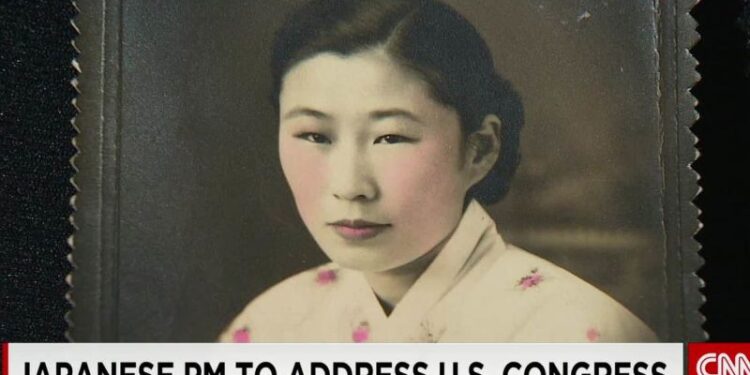

Kim Bok-dong is determined to share her story of sexual slavery until she’s no longer physically able

Kim was held prisoner by the Japanese military in a “comfort station” for five years, raped ceaselessly

She says she won’t rest until she receives a formal apology from the Japanese government

CNN

—

Kim Bok-dong is 89 now, and is going blind and deaf. She knows her health is fading, and she can no longer walk unassisted. But her eyes burn bright with a passion borne of redressing her suffering of a lifetime ago.

She enters a meeting of Tokyo foreign correspondents in a wheelchair, visibly exhausted after a flight from Seoul and days of interviews and meetings.

The nightmares from five years as a sex slave of the Japanese army, from 1940 onwards, are still crystal clear. Kim is determined to share her story with anyone who will listen, until she’s no longer physically able.

“My only wish is to set the record straight about the past. Before I die,” Kim says.

Kim was a 14-year-old girl when the Japanese came to her village in Korea. She says they told her she had no choice but to leave her home and family to support the war effort by working at a sewing factory.

“There was no option not to go,” she recalls. “If we didn’t go, we’d be considered traitors,”

Instead of going to a sewing factory, Kim says she ended up in Japanese military brothels in half a dozen countries. Along with about 30 other women, she says she was locked in a room and forced to do things no teenage girl – no woman – should ever have to do.

Kim describes seemingly endless days of soldiers lined up outside the brothel, called a “comfort station.”

Often they were so close to the front lines, they could hear the battles of World War Two happening all around them.

“Our job was to revitalize the soldiers,” she says. “On Saturdays, they would start lining up at noon. And it would last until 8pm. There was always a long line of soldiers. On Sunday it was 8 a.m to 5 p.m. Again, a long line. I didn’t have the chance to count how many.”

Kim estimates each Japanese soldier took around three minutes. They usually kept their boots and leg wraps on, hurriedly finishing so the next solider could have his turn. Kim says it was dehumanizing, exhausting, and often excruciating.

“When it was over, I couldn’t even get up. It went on for such a long time. By the time the sun went down, I couldn’t use my lower body at all. After the first year, we were just like machines,” she says.

Kim believes the years of physical abuse took a permanent toll on her body. Tears stream down her cheeks as she explains how she was never able to fulfill her dream of having children.

“When I started, the Japanese military would often beat me because I wasn’t submissive,” Kim says.

“There are no words to describe my suffering. Even now. I can’t live without medicine. I’m always in pain.”

Kim is part of an NGO called the “Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan,” which is fighting for an apology.

Some Japanese prime ministers have personally apologized in the past, but the NGO director believes that it’s not nearly enough.

Tokyo maintains its legal liability for the wrongdoing was cleared by a bilateral claims treaty signed in 1965 between South Korea and Japan.

Kim’s story matches testimony from other so-called “comfort women.”

In Washington, as Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe conducts a state visit to the United States, former Korean sex slave Lee Yong-soo makes a tearful plea to him, demanding an official apology for Japan’s sexual enslavement of an estimated 200,000 comfort women, mostly Korean and Chinese. Many have since passed away, but those still alive want individual compensation for their treatment.

Critics say Abe has not been vocal enough. They fear his government is trying to whitewash the past, to appease conservatives who feel comfort women were paid prostitutes, not victims of official military policy.

“When it comes to the comfort women sex slave system, it is pretty much unique to Japan. I think Nazi Germany had some of it to a smaller degree. But in the Japanese case it was large scale, and state-sponsored, essentially,” says Koichi Nakano, a professor of political science at Tokyo’s Sophia University.

Nakano points out that, since Abe first came to office his government has succeeded in removing references to “comfort women” from many Japanese school textbooks.

It’s part of what critics call Japan’s track record of glossing over its war crimes.

“(Comfort women) have gone through tremendous trauma. And in a way, the Japanese government risks a second rape by discrediting their testimonies and treating (their experiences) as if they were lies,” Nakano says.

Abe insists he and other Prime Ministers have made repeated apologies.

“I am deeply pained to think of the comfort women who experienced immeasurable pain and suffering,” Abe told diet lawmakers last year.

Abe gave a similarly worded statement during a press conference Tuesday in Washington, DC – leading critics to question the sincerity of Abe’s expressions of remorse over the issue. Abe has said he does not believe women were coerced to work in the military brothels.

Nakano says Abe and conservative lawmakers feel “singled out.”

“They feel there’s some sort of a plot by other Asian countries to sully the Japanese name to their advantage.”

With Abe’s historic visit to the U.S. just months before the 70th anniversary of the end of World War Two, Kim wants President Obama to pressure his key Asian ally to do more to acknowledge history.

Meanwhile, Kim has had enough of the excuses she says are hampering her efforts to finally get peace.

“To say there’s no evidence is absurd. I am the evidence,” she says.

Discussion about this post