Should China be invited to this year’s G7 summit in France? Kenddrick Chan and Chris Alden write that treating the G7 as the core node of global governance risks turning a blind eye to where influence actually lies and where meaningful cooperation with China is most likely to occur.

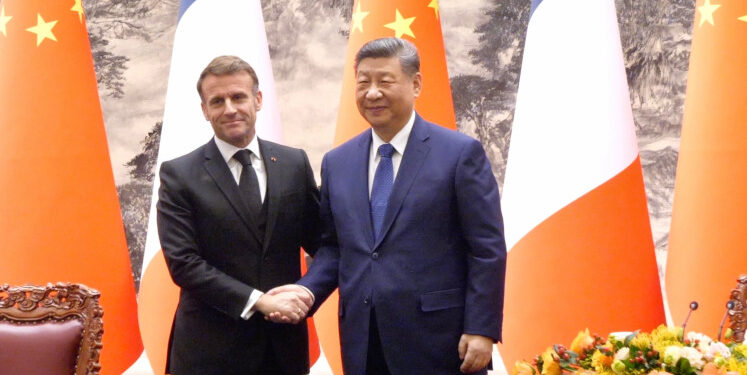

Prior to his visit to China at the end of last year, French President Emmanuel Macron floated the idea of inviting China to the 2026 G7 summit in France. The immediate reaction from fellow G7 member Japan was one of unease. Yet debates over this proposal risk missing a fundamental point.

If half a century of interaction between China and the G7 teaches us anything, it is that the problem has never been one of access. Instead, it is one of relevance as China continues its march to great power status. The truth is that China sees the G7 as largely irrelevant and an invitation to join is unlikely to change that.

China and the G7

Since its inception in the mid-1970s, the G7 has functioned as an informal steering committee of the global economy. It brought together the world’s leading economies at a time when global economic power was concentrated within what was broadly termed “the West”, including Japan.

China, then just emerging from the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, was only just embarking on the nascent phase of its “reform and opening up” effort and stood well on the outside. Yet exclusion alone does not explain Beijing’s subsequent approaches towards the grouping. Even during periods where China and the G7 shared more common ground than today, Beijing has repeatedly declined deeper institutional engagement with the G7.

Rapid Chinese economic growth and its stabilising role during the Asian Financial Crisis, coupled with the global development agenda of the 1990s, saw growing G7, and later G8, interest in deeper engagement.

However, outreach efforts such as the Heiligendamm Process fell short of granting emerging economies (including China) a meaningful role in agenda-setting. From Beijing’s perspective, these arrangements reinforced a perception of the G7 as a western-dominated forum in which it fundamentally would be a member of the audience than an agenda-setter.

This was not simply a matter of diplomatic pique resulting in ruffled feathers or bruised egos. Chinese reluctance at deeper G7 engagement is rooted in ideology, identity and influence.

Historically, Beijing positioned itself as a champion of the developing world, first through the language of Third World solidarity and later through the broader banner of the Global South. Deeper institutionalisation within the G7 would have cut against this self-conception, blurring the distinction between North and South that has long underpinned Chinese diplomacy.

Institutional diversification

The hope that China could be socialised into the existing western-led order through inclusion is not new. Macron’s faith in “acting together” with Xi echoes a past tradition.

In the early 2000s, the idea of China as a responsible stakeholder rested on the belief that deeper engagement with western-led institutions would bind Beijing more closely to the existing order. Macron’s inclination is intelligible, given that global cooperation on issues such as climate change remains indispensable.

However, the assumptions underpinning such logic deserve closer scrutiny. China does see itself as a responsible actor in global governance – just not on the terms of the G7. Over the past two decades, it has methodically constructed and contributed to parallel institutional arrangements that collectively reflect its growing economic heft and preference for a more pluralistic international order.

The creation and expansion of the BRICS grouping, establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the scale of development finance provided by Chinese policy banks have given the Global South alternatives to G7-led development initiatives. In doing so, China has avoided operating within western-defined parameters and hierarchies to project influence and shape global development agendas.

Such institutional diversification also occurs at a time of profound shifts in the global economy. In the decades since the G7’s conception, the combined share of its economies has fallen markedly, while emerging economics (with China at the forefront) command an ever-increasing proportion of global economic growth. The elevation of the G20 after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis aptly captures this changing of the guard.

The limits of the G7

Seen from Beijing, the G7 appears less like the cockpit of global economic governance and more of a values-aligned caucus – and even that is increasingly fragmenting under the Trump administration.

The shift in recent years towards emphasising shared norms and values may have been intended to strengthen cohesion among its members, but it comes at the cost of a narrowed scope for meaningful engagement with those who do not align on the same ideological foundations. For China, participation in the G7 offers limited practical returns.

None of this, however, is an argument against dialogue with China. History shows that cooperation has been possible and productive when discussion occurs in forums where influence is more equitably distributed. The lesson of the past 50 years is that invitations alone neither confer relevance nor reverse structural changes in the international economic order.

The greatest danger for the G7 moving forward is not that China will refuse to engage with it, but that its members misunderstand the very real limits of what the forum can now achieve. Treating the G7 as the core node of global governance risks turning a blind eye to where influence actually lies and where meaningful cooperation is most likely to occur.

Kenddrick Chan and Chris Alden are co-authors of “China and the G7” in The Elgar Companion to the G7 (Edward Elgar, 2025).

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of LSE European Politics or the London School of Economics.

Image credit: Vernerie Yann provided by Shutterstock.

Discussion about this post