Moldova entered the 2020s as one of Europe’s most depopulated countries. Diego Muro, Géza Dobó and Robert Gönczi write that Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has simultaneously accelerated Moldovan emigration and redirected Ukrainian mobility into Moldova, producing a two-way corridor with lasting social, economic and political effects.

The 2024 census confirmed what Moldovans have felt for years: the country is shrinking. The resident population has fallen by 13.6% over the past decade, with a diaspora exceeding a million people, larger than the country’s domestic workforce.

Economic decline, low wages and a demographic profile tilted toward ageing and depopulation have combined to hollow out the countryside. The war next door has added both urgency and contradiction to Moldova’s migration landscape. The war in Ukraine has transformed Moldova from a primary sender of people into a simultaneous sender and receiver.

Ukraine as the variable – channels of impact

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reshaped Moldova’s migration map almost overnight. The Odesa–Chișinău corridor became a lifeline, turning a country long defined by outmigration into one of simultaneous departure and arrival. Many Ukrainians moved on, but others stayed in Moldova, drawn by proximity and shared language.

Russian remains a common bridge language, despite ethnic Russians being a small, urban minority, a legacy of the Soviet era. Moldova’s internal fractures also persist: Transnistria remains a frozen conflict and Russia’s foothold in the region, while Gagauzia, the autonomous region populated by Orthodox Christians of Turkic origin, remains discontented with Chișinău’s authority. Alongside demographic decline, managing these unresolved minority issues is Moldova’s other central challenge

The war’s disruptions have spilled across the border. Each wave of Russian airstrikes, drone attacks, blackouts and economic shocks in southern Ukraine sent new flows westward, showing how closely Moldova’s mobility patterns mirrored its neighbour’s instability. Yet Moldova’s role remained mostly transitory: while EU states offered stronger legal protections and higher wages, Moldova provided temporary safety and solidarity but few long-term opportunities.

The great escape – why Moldovans still leave

Since independence from the Soviet Union, Moldova has lost close to half its inhabitants, with the population declining from 4.36 million in 1991 to roughly 2.4 million in 2024. Every year tens of thousands of Moldovans cross the border permanently or for long-term work abroad.

The reasons are clear. Moldova remains one of Europe’s poorest states, burdened by weak wages, limited opportunities and an ageing workforce. As young people leave, entire rural districts fade away.

Large-scale labour migration has given rise to so-called “video chat families”, households that sustain their relationships through digital screens rather than shared physical space. In many rural areas, this phenomenon has left a generation of children to be raised by grandparents or by a single remaining parent. As physical proximity is replaced by video-chat parenting, these children face an emotionally demanding situation marked by distance, longing and fragmented family life.

Moldova’s household economy is also heavily shaped by labour migration, with remittances accounting for approximately 12.3% of GDP, one of the highest ratios in Europe. Comparable patterns can be observed elsewhere, such as among African migrants in the United Kingdom and Latin American communities in the United States, where transnational family structures also rely on income earned abroad.

From outflux to influx

As tens of thousands of Moldovans continue to pack their bags for foreign destinations, another demographic tide has begun to flow in the opposite direction since the outbreak of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. From February 2022, Moldova absorbed more refugees per capita than any other country in Europe, with over 800,000 crossings recorded in the first nine months of the war.

At first, Chișinău viewed the inflow as an opportunity: retaining part of the Ukrainian labour force could soften the impact of Moldova’s mass emigration. Yet low salaries quickly dashed those hopes. The average net monthly pay in Moldova (around €530 in 2024) still lags far behind even the EU’s lowest earners. Many Ukrainians, initially open to staying, eventually moved on to EU member states where conditions were more favourable.

A new, wealthier wave soon replaced them: Ukrainian entrepreneurs who continued running their businesses in their mother country but sought a safer base nearby. This group has quietly reshaped the housing market.

While rural Moldova is dotted with tens of thousands of abandoned houses – some selling for under €5,000 – in the capital Chișinău, prices for high-quality and well-located apartments have doubled or even tripled since 2022. Limited new construction amplified the squeeze, turning the capital’s upper-segment property boom into one of the country’s most visible war-related paradoxes. This has effectively created two Moldovas: one prosperous and urban, the other rural and forgotten.

War-shaped pressures on a fragile state

The conflict in Ukraine has intensified Moldova’s existing demographic and economic fragility. Outmigration continues to drain the country’s workforce, leaving hospitals, schools and farms understaffed. At the same time, the inflow of Ukrainian refugees has added pressure on already limited welfare systems.

Migration and war have combined to heighten Moldova’s geopolitical exposure. The country sits on the EU’s eastern flank, sharing a border with a war zone. Each movement of people thus carries political weight: Moldova’s ability to manage migration is now inseparable from its security and its European ambitions. A half-empty state finds it harder to implement Brussels-driven reforms, making demographic resilience an issue of national survival.

Turning shock into resilience

If Moldova is to turn this demographic shock into an opportunity, it must move from short-term reception to long-term retention. The country has proven capable of managing an emergency inflow with limited resources. The challenge now is to make staying attractive for both Moldovans and Ukrainians. That requires raising wages and improving living conditions.

Equally important is investing in the places that still hold people. EU funds and domestic programmes should prioritise midsize towns rather than concentrating on the capital Chișinău. Affordable childcare, vocational colleges and digital public services could help younger families see a future at home instead of abroad. This would not only slow depopulation but also rebalance Moldova’s territorial inequalities, anchoring growth beyond the capital.

Moldova’s large diaspora should be seen as an asset, not a loss. Policies that enable circular migration – including tax incentives, portable pensions, remote-work schemes and diaspora bonds – can keep talent connected to the country.

Staying power – between exodus and resilience

Moldova’s demographic exodus didn’t begin in 2022, but the invasion of Ukraine re-wrote the script. An external shock turned a one-way exodus into a two-way corridor, amplifying existing weaknesses and creating narrow opportunities. The country is now both a place to leave and a place to land, often for people shaped by violent conflict.

Whether this moment produces resilience or deeper fragility will depend on policies that shift from short-term emergency responses to long-term integration. If Moldova can convert the exodus into people who stay, return or circulate, the war next door might stop the shrinking of Moldova.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of LSE European Politics or the London School of Economics.

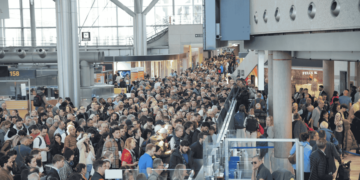

Image credit: Sergio Delle Vedove provided by Shutterstock.

Discussion about this post