This year was billed as “the year of elections” due to the number of major elections taking place across the world. Michael Cox writes that while many of these elections have been turbulent affairs, we should not forget that democracy, warts and all, remains the political system of choice for most countries in the world today. But he concludes by asking: will this remain so forever?

The year 2024 will probably be remembered best by political scientists as having been a great year for democracy, with more voters than ever in history having gone to the polls in at least 64 countries. That at least is the good news.

However, if one of the purposes of free and fair elections is to allow for a relatively stable transition of power, it has certainly not worked everywhere. Bangladesh is a good example of where it failed. Nothing ever seemed to go right. First, the main opposition party boycotted the poll in January. This was followed by political unrest. And in August, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina fled the country following deadly protests.

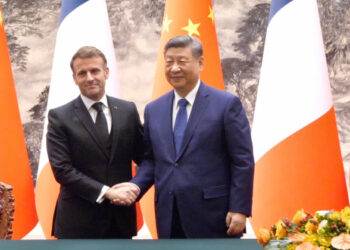

Nothing as dramatic happened in Europe. Here in fact pro-EU parties still held on to a majority in the European Parliament. Nevertheless, populist, nationalist and far-right parties did make gains. Meanwhile, in both France and Germany, uncertainty reigned as first Emmanuel Macron and then Olaf Scholz came under intense political pressure at home. Indeed, so uncertain had the political situation in both countries become by the end of the year, that some feared for the future.

Then of course there were the presidential elections in the United States in November. At one level, the election was a model of democratic propriety. Yet even if over 150 million citizens voted, not for one minute did anybody believe that order was about to return to what many were now referring to as the “Disunited States of America”.

More discord then followed in Romania when after the first round of voting in the presidential election, its constitutional court annulled the vote on the grounds that there had been outside interference. Meanwhile, in Georgia, elections held in October were still generating controversy and protest on the streets of the capital Tbilisi six weeks later.

Indeed, the only elections which appeared not to generate division and discord were those held in the UK in July and in Ireland in November. Not for the first time in history have the two islands sitting off the coast of mainland Europe managed to buck the trend!

Back to the future?

Perhaps we should not have been surprised by any of this. With inflation cutting into living standards worldwide, inequality rising, immigration pressures continuing, trade uncertainty threatening growth, the Middle East in flames, Ukraine at war, much of the Global South in ideological revolt at what they see as the North’s double standards, and Russia under Putin and China under Xi working together in a bid to upend the western-led “rules based order”, we are not exactly living in normal times.

If we then add to this what looks like (or is alleged to be) interference on an almost industrial scale into European politics by Russia, it is hardly surprising that many pundits are feeling gloomy about democracy’s future. Some even believe we are teetering on the brink of something more terrible still. This certainly seems to be the view of Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, who has for a while been claiming that we are facing nothing less than a “1938 moment”, one that might very easily spill over into something much worse in the future.

Reasons for – guarded – optimism

With so much that is going wrong right now, it is easy to be pessimistic. Indeed, pessimism itself has now become intellectually fashionable in the West, quite a contrast to how people felt in the immediate post-Cold War years when Europe was at peace, America was led by a formidably intelligent liberal in the form of Bill Clinton, and globalisation looked like providing most of the answers to the world’s economic challenges.

One would also have to be intellectually blind not to see that democracy is under stress. In fact, book after book over the past few years has been talking about little else. But we should beware assuming it is on the point of collapse, or that we are in a late 1930s “moment”.

Take Russia under Putin. There is no question it is dangerous and belligerent. But then so was the former Soviet Union which was just as repressive (if not more so) and had no hesitation in invading countries like Finland (1940), Hungary (1956) Czechoslovakia (1968) and Afghanistan (1979) when they deviated from the “general line”.

China meanwhile is self-evidently a challenge to liberal democracy; and according to Xi no less, a genuine alternative to what is on offer in what he sees as the “declining West”. But even China – even under Xi – has a huge stake in the current world economic order. It also faces major challenges of its own including high unemployment amongst its graduates, a collapse in the property market and most significantly, a slowdown in growth.

Nor if the democracies are looking for some hope in these unsettled times, is the Europe of today the disaster it is often portrayed as being. The problems facing it are, as we have seen, all too real. But compared to where it was in the interwar period, not to mention the Cold War, it is in much better shape right now. Not only is it wealthier and more peaceful than it has ever been before – though you wouldn’t know it if you read some accounts – support for democracy across the continent and indeed for the EU itself remains extraordinarily high.

Best of the worst

We are no doubt living in some very turbulent times which, as we have shown, many democracies are finding it very difficult to navigate successfully. But we still need to remind ourselves as we gaze forward into the unknown, that at the start of the twentieth century there were hardly any democracies, three quarters of a century later there were still less than 50, but today there are around 130.

Admittedly, even the best democracies are imperfect. Moreover, in a world subject to huge global pressures it is fair to ask – and Erica Benner asked it in her most recent book – whether a form of government based on endless debates among quarrelsome, sometimes misinformed, more often than not self-interested citizens, is up to the challenge?

Benner offers no easy answer. But at the end of the day, she believes it is, but only once we all stop selling the idea that voting in even the freest and fairest of elections is going to solve all our problems. To quote Benner herself, “binding democracy to progress can encourage a dangerous hubris”. This is no doubt true.

Still, if it is to survive into the twenty first century, democracy has to deliver a whole lot more than it is doing right now. As we have indicated here, if 2024 points to anything, it is that democracy remains widely popular, the “best of the worst” forms of government, as Churchill is once reported to have quipped.

But the question remains: can it survive intact if it fails to deliver on what the majority of people appear to need most – a fair crack of the economic whip, decent healthcare, and everyday security. If it does deliver on this bare minimum, it may well survive. But if it fails to do so, then we can reasonably ask: what follows if or when it doesn’t?

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: LCV / Shutterstock.com

Discussion about this post