A no-confidence vote triggered by a dispute over the French budget has led to the collapse of the country’s government. Camilla Locatelli writes that France’s fiscal challenges offer important lessons for the rest of Europe.

On 4 December, the French government collapsed after Prime Minister Michel Barnier lost a vote of no confidence. The vote was called after Barnier used Article 49.3 of the French constitution to force a social security financing plan through parliament without a vote.

The government, which had only been in power for three months, found itself at a difficult crossroads when it came to passing a budget. The country’s deficit for 2024, which was initially forecast to be 4.4%, was later revised upwards to 6.1%. This revision raised serious questions not only about the state of France’s public finances but also about how it was possible that the worsening budgetary situation had been able to fly under the radar for so long.

Weak oversight and optimistic projections

It may seem strange to international observers that the budget figures have turned out to be unreliable. For French observers, however, it is well known that French budget estimates have tended to be overly optimistic in recent years. On several occasions over the past decade, the French Treasury has overestimated growth projections, particularly in relation to compliance with EU fiscal targets.

My doctoral research focused on this issue. I found that France managed to escape much of the pressure from EU fiscal rules during the 2010s by playing with the technical estimates used by the EU fiscal surveillance system. Thanks to the French Treasury’s technical expertise and the relative weakness of domestic surveillance mechanisms, France managed to convince the European Commission that its budget figures were realistic, even when there were clear signs French growth had been overestimated to justify higher public deficits.

An oversight body, known as the Haut Conseil des Finance Publiques (HCPF), was set up in 2012 to monitor the government’s budget figures as required by the EU’s fiscal compact, but its capacity and independence have been limited. The lack of external and domestic oversight has allowed the budget situation in France to be misrepresented. A parliamentary commission is now investigating how this situation was allowed to develop.

What now?

France now faces three main problems. First, business tax cuts in the name of competitiveness have shrunk the tax base. During his first term, President Macron oversaw a reduction in the corporate tax rate from 33.3% to 25%, lowered mandatory tax contributions paid by French companies and abolished the country’s wealth tax. These tax cuts only had a short impact on growth yet have reduced revenue. As Jean Pisani-Ferry, one of those who developed this approach, put it in a recent interview, “in principle, it wasn’t a bad strategy, but it didn’t work”.

Second, Macron’s commitment to spend “whatever it costs” during the COVID-19 pandemic led to an explosion in public spending, partly financed through the EU’s NextGenerationEU programme and sustained by a large domestic spending plan called France Relance.

While this did protect the French economy during the worst of the crisis, it was hugely expensive and mostly focused on cushioning businesses from the most acute, short-term effects of the shock. This expenditure did not address the French economy’s structural issues of low growth through long-term interventions such as large-scale public investment.

Third, after two decades of blind trust from financial markets, France is now experiencing higher borrowing costs. In September, French bonds were traded at a higher interest rate than Spanish bonds for the first time since 2008. In October, the ratings agency Moody’s downgraded France’s economic outlook from “stable” to “negative”.

At the end of November, French borrowing costs had reached an unprecedented high, close to the levels seen at the height of the sovereign debt crisis and above those of Greece for the first time. This reflects a loss of credibility for the French public finances in the eyes of international creditors and will make it even more difficult to address the current crisis.

Lessons for Europe

These issues landed in the lap of Barnier, who was faced with the prospect of putting together a budget that could address every problem simultaneously. He had to find a solution without a political majority and without the support of the opposition on either the far left or far right. He tried to achieve this by means of an austerity budget with plans to cut public spending by 60 billion euros. It is little wonder that he failed to do so and that France’s fiscal crisis has now turned into a political crisis.

Yet the chaos around the French budget also highlights many issues connected to the EU’s system of fiscal governance. The lesson from this experience is not that the EU should make the rules stricter for countries like France, but that a decade of strict fiscal rules has failed to achieve both fiscal discipline and fiscal surveillance. EU rules have also failed to create credibility in financial markets, which remain volatile and linked to political dynamics rather than fiscal fundamentals.

At a time when growth projections for most Eurozone economies look bleak and the EU’s fiscal rules are coming back into force (even for Germany – the main advocate for stricter rules), the French experience should prompt a reassessment of whether the full application of these rules is really the best way to address the current economic challenges facing EU economies.

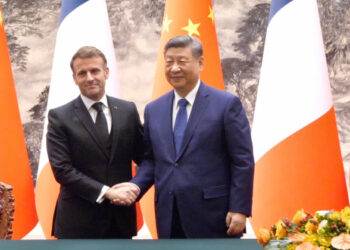

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Antonin Albert / Shutterstock.com

Discussion about this post